The Exquisite Loneliness of Northern Exposure

What can a lost TV show from the 1990s teach us about life today?

It’s been a few weeks since I published a story… summer break got in the way. So here’s a longer than usual piece I’ve been working on for a while, about the rebirth of one of my favorite TV shows.

Have you ever moved to a place where you didn’t know anybody? The closest I’ve come was when I moved to Los Angeles, two and a half decades ago, and joined my brother here. He was the one person I knew. I would say I “immigrated”, but at the time I didn’t realize that that was what I was doing. It felt more like some time off. A break from life as I knew it in my Australian homeland.

I needed space. It wasn’t a new feeling. I had moved away for my first year of university at the age of 17, to a campus just an hour’s drive from my childhood home, Melbourne. Then to Sydney for a semester. The US, too, never felt very far away. All you had to do was turn on the TV. In early adulthood, bouncing between those Australian towns, I’d developed a strong affection for a handful of American TV shows, which I still feel.

Most of my close friends loved The Simpsons, and we still quote it to this day. The other popular show I fell for was Seinfeld. During high school a stoner friend and I bonded over it immediately, when its first season ran late at night on Australian TV. Recently I indulged the wonder of modern streaming by rewatching the entire run over some months. One other show that hooked me in those years was Northern Exposure. A little more obscure, and after its first few airings it disappeared off of TV schedules completely.

Northern Exposure first aired between 1990-1995. As our rapidly technifying world jolted into the 2000s, I would look for ways to rewatch the show on occasion. Video cassette copies were staggeringly rare, reruns unheard of, and online rumors abound regarding song licensing complications.

Though I did eventually discover some episodes on YouTube, the audio had been slowed down to a near slur and the picture often obscured, to evade autonomous copyright searches. It was no fun to watch. Like the fictional town of Cicely, Alaska within which it is set, Northern Exposure unwittingly remained at arm’s length from a rapidly modernizing outside world.

Now a decade after streaming services became the norm, Northern Exposure has finally taken its place in TV’s bulging digital cabinet, available to US subscribers of Amazon Prime Video, in all its fuzzy, filmic glory. I was so excited by the discovery that I tried to convince my wife — who works for the streamer — they should be marketing this faded but blessed rebirth, aggressively.

I dove right back in from Episode 1 and have been making my way through the seasons ever since. I was excited to begin, but wary, too. Unsure of how I would feel if my fond memories were shown to be unwarranted, and the show wasn’t so good after all. How well you can trust the taste of your younger self feels undetachable from the many other, more plain and humbling realties of middle-age.

There’s something otherworldly about revisiting a TV show after all this time. I vaguely remembered storylines and characters, and had inflated some narratives in my mind, while minimizing others. Some of the themes (most noticeably regarding sex and sexuality) are predictably out-of-date. While others (particularly around Indigenous representation) if not note-perfect, feel comfortingly prescient. All in all I still enjoy the show very much and continue to devour its many episodes.

But what has struck me most about Northern Exposure during this revisit, is the elemental loneliness of the show and its protagonists. This may not be helped by the fact that I myself often watch episodes (or parts of them) alone, after the people in my house who quite reasonably couldn’t care less about this ‘90s relic, have gone to bed.

Out of the show’s nine main characters (in case you watch, I’d classify them as: Joel, Maggie, Chris, Holling, Shelly, Maurice, Ruth-Anne, Ed and Marilyn), only two are in an ongoing relationship (with each other) and none have children in town. Joel’s early engagement to a New Yorker ends quickly under the strain of becoming long-distance. A strain felt by the character as much as the show’s writers, I assume. Partners come and go sometimes. Joel and Maggie play TV’s old Will-they/Won’t-they game to middling effect. But only Holling and Shelly would identify as anything other than single.

It’s occurred to me that this device serves to further emphasize the community’s need for each other in such a remote place, and forces the characters into contact and conflict. They can’t simply pair-off into self-sustainable family pods. But as the hours of watching have ticked by, that feels too convenient an explanation. Something one might hear in a freshman scriptwriting class. There’s more to it, I feel, about what the show (or its creators, at least) may have to say about life.

My other favorite shows from the era — Seinfeld and The Simpsons — portray common types of families. Both the kind you make with your friends, and the classic TV nuclear family. The 1990s was the last full decade before the social media era began. A time when being together truly meant being together. The Covid pandemic changed a lot of things in society, but it also simply accelerated existing trends. One of which was the diminishing priority we put on seeing each other in real life (or “IRL” as the experience is reduced to online). The wholesale devaluation of anything resembling a physical community. Dividing people is how politicians and corporations most often thrive. We have never been more separate.

In its own dreamlike, analog way, Northern Exposure somehow presaged this shift. What the show foretells, I feel, is that eventually we could all be marooned by modern life. Stuck in our own digital Cicely, without the vistas, or warmth of its humanity.

Joel, a freshly-minted doctor, is forced to work in this place, far from his beloved New York City. He agreed to the arrangement with the State of Alaska, in order to subsidize his medical degree. But he was promised work in a city hospital, not the dilapidated storefront of a one-horse town. He is set adrift, isolated from his people and, more obviously, feels cheated. We see that from the very first episode — ranting at anyone who’ll listen — and he reminds us of it constantly throughout the show. He won’t accept the change, or integrate into a community he sees as beneath him. Instead complaining incessantly and wearing his marooning as a hair shirt.

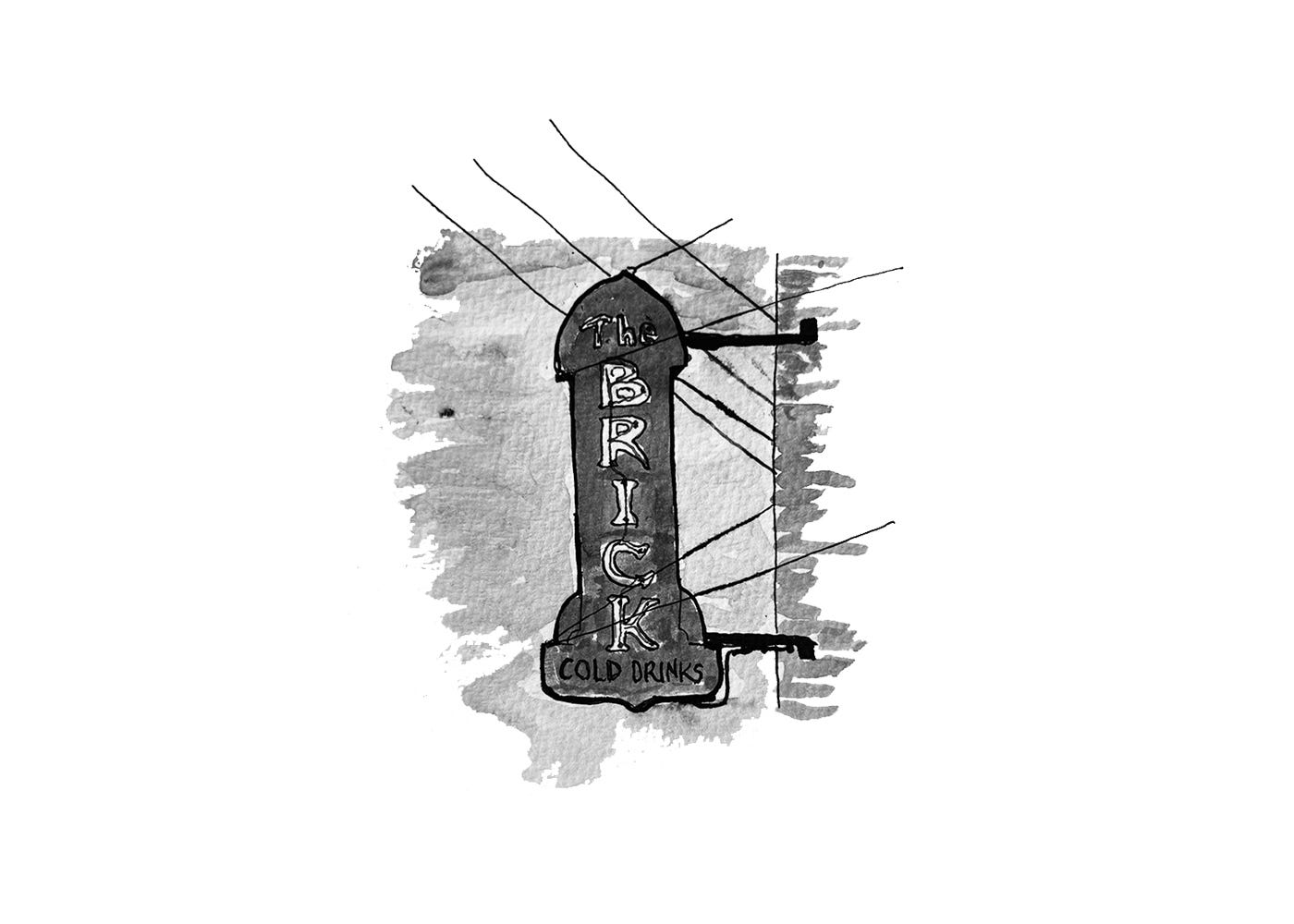

Much like The Simpsons or other cartoons, the main characters of Northern Exposure exist in an almost static state. Trapped in an aging-free, under-the-microscope world. Bills aren’t much spoken of, appetites are easily met at Holling’s bar The Brick, and friendships and rivalries fluidly switch between people who are somehow wed to this seemingly industry-adjacent location. (Is it a logging town? A farming hub? A tourist attraction? Rare is the solid clue. Cicely just is.) Life moves fast, we’re always told, but not to these characters. Living so much online can feel that way, too. As if everything is happening all at once, only it’s happening to other people. Not you. You’re just glued to the eyeglass. Going nowhere.

As a younger man I didn’t look unlike Joel Fleischman. I’m not Jewish, or from New York, but I have the nose for the job, somewhat of the ‘fro, too, and my big city upbringing and outsider status in Los Angeles has definitely resulted in a noticeable dose of his cynicism. Was his exile what first appealed to me about the show? His loneliness, too? The character himself isn’t particularly likable (which may explain why, in an era before “difficult” central characters, the actor Rob Morrow found scant work), yet the show still manages to loosely revolve around him, at least in the first few seasons. We get to know Cicely through his lonely, bewildered wanderings.

Loneliness is one of those topics that therapists can have a field day with. Most commonly because we tend to associate it with being alone, rather than merely feeling alone. A person can easily feel lonely in a crowd, and I have on numerous occasions, particularly when I was younger.

Northern Exposure marinates its characters in loneliness, even when they’re elbow-to-elbow, sharing a beer at The Brick. Yet we watch them carry on, quite happily most of the time, perfectly pleased to see one another when they must. People there are often shoe-horned into social situations, despite their loner tendencies, typically with joyful results. Joel waxes lyrical about the lack of progress in Cicely, whilst being drawn further and further into what he often derides as the town’s backwards culture.

In one episode, Joel is literally kidnapped by a couple, deep in the woods, but eventually gives up trying to break his shackles. Instead sharing their surprisingly good food and offering blunt marital advice, before leaving without ever alerting the authorities. In another, he is told – point blank – that he has no friends in town, and then throws a party at his house, in an attempt to improve his social connections.

A recurring theme for Maurice is his rage over Holling “stealing” his young, beauty-queen girlfriend, Shelly. A romantic and domestic hole in his ego he struggles unsuccessfully to fill, season to season, in his uniquely American, capitalist god-of-unlikability kind of way. Buying too much, giving up so little, infuriated all the while by the minions who never seem to appreciate all he has done for them. Childless (but for a rarely sighted, accidental adult offspring) he embodies the bitter loneliness of an estranged parent and addicted capitalist fully. Resenting the townsfolk for not recognizing all that his alleged suffering and intellect has brought their lesser selves. Wrestling with his loneliness, whilst still choosing it over any other of his many options.

Maggie – despite her Moonlighting-esque flirtations with Joel – is renowned for the men she dates dying on her. It bothers her, of course, but ultimately, resourceful and handier with a tool than ninety percent of the show’s men, she seems okay alone. Like it’s meant to be.

In fact, everyone on Northern Exposure is, in their own way, happy alone. In another episode, Ruth-Anne’s son comes for a rare visit. He is her opposite: she a small town shopkeep, who paints on the side; he a big city stockbroker, with no time for hobbies. Now he’s feigning a renewed interest in humble pursuits like fly fishing, only to fall in with Maurice and a mountain of fresh bookkeeping on a stowed-away laptop. She sees their distance as healthy and can’t wait for him to leave, which he eventually does.

At night, when not at The Brick, characters host intimate dinners or simply read a book. Or, in the case of budding film director Ed, watch a VHS. Other than that, anything as modern as a TV is almost invisible. In a sense, their loneliness is their companion, and not even the still-smitten-after-all-these-months Holling and Shelly see eye to eye most of the time. They need their space from each other, too. She repeatedly sends him on camping trips with glee.

Still, unlike many of us in the digital era, the characters always find a way to come together. The goofy neighbor might not burst through your apartment door at any given second, or spout bible verses from over a well-manicured hedge, but they’re out there. Just a chilly walk or a truck ride away.

Ordering dinner to be delivered to your door on a whim, or catching the latest movie right on your couch, aren’t options. Let alone cutting someone out of your life because things got rough, or awkward, at some point. You’ll run into them again soon enough. Or need their particular and unique personal resource, just when you least expect it. The community of Cicely is interdependent, unpredictable and alive in a way we’ve come to fear. These loners still need each other, so they find a way to get along.

Loneliness is a personal condition, after all. It doesn’t mean you don’t like people. Sometimes it’s the opposite. But people are like alcohol that way; our love for it might be the same, but our tolerances will differ. Everyone has to find their very own balance. Still, going cold turkey on people just isn’t a realistic option.

Between its release in 1990 and re-airing 34 years later, Northern Exposure suffered a cultural death in a way my other favorite shows didn’t. The flame wasn’t kept alive by the series remaining in production (like The Simpsons, incredibly) or transferring to rounds of never-ending syndication and streaming (like Seinfeld and many more). Everyone at my wife’s work simply describes Northern Exposure as a show their parents were probably into, thrown into the streaming library for old timers like me to enjoy.

In that way it speaks to its handful of viewers from beyond the grave. From a time before smartphones and time sucking apps and a global pandemic, and a further digital pandemic of aloneness. A knowing and seemingly ancient voice.

Don’t give up on your friends and neighbors, it whispers via the old 4:3 screen ratio, over helicopter shots of figures wandering a boundless wilderness. Small towns in remote places like Alaska are, after all, synonymous with solitude. As are the spaces we so often virtually inhabit now.

These places might attract the lonely, but it doesn’t mean we have to be alone.

A great analysis of a show Toby. Unfortunately, I grew up totally without television, in fact didn't own a TV till I was in my late forties, so I missed this show entirely. Only bought one then because we had to find a distraction for my daughter's overactive mind.